Mid-century: A Thriving and Loving Community

Cummings Street, 1966. Photo credit: Spartanburg County Public Library

Photo of Black faculty of Spartanburg Public Schools. Emerson Coleman and C.C. Woodson, side-by-side, third and fourth from left. Photo credit: Vicki (Coleman) Hogan

According to its residents, the keynote of the Back of the College neighborhood was community. Without fail, former residents of the neighborhood interviewed for this project talked about the experience of being raised in a loving community. Judy Hutchinson speaks for many when she says, “[i]t was a loving community. Everybody was a family. Right? All us stuck together. Just like it say, it takes a village, you know, to raise children. That’s how it was back there. The whole village.”

Doris Posey emphasizes feeling safe growing up, a feeling created by the neighborhood’s cohesion: “we were so safe. We were very safe. When people talk about the village, we were the village. We were very lucky children…we have a lot of people to thank for that environment. We really do.” Sherry Wiggleton agrees: “We used to sleep on our front porches. We sleep on our front porches, we can leave and go to town and come back, our doors unlocked. Ain't nobody broke into your houses. I mean it was just, it was just such a lovely community back then.”

Posey attributes the community feeling in the neighborhood to the character of its residents. “But I think the adults had the right state of mind. And they weren't trying to work together. They didn't have some big plan for the neighborhood or the children in the neighborhood to be just great children and come out right. They had good character. And it passed down to us. We had the benefit of their good character. A lot of them uneducated, a lot of them doing menial jobs. A lot of them maybe had never left their own state, you know, but they were good character. And we were the beneficiaries.”

Louvenia Barksdale receiving an award. Photo credit: Bertha Johnson

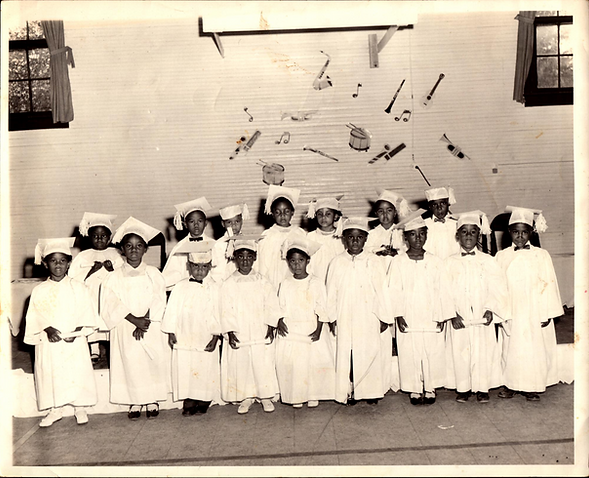

Pageant at Kiddie College pre-k/Kindergarten, 1959. Photo credit: Norma (Foster) Green

May Day Parade, Cummings Street, 1967. Photo credit: Norma (Foster) Green

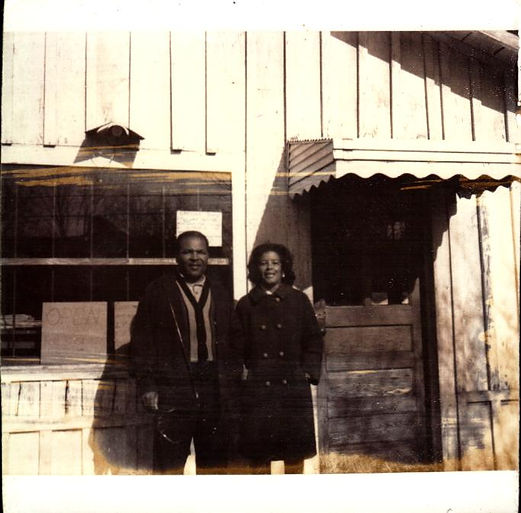

The Fosters at their store. Photo credit: Norma (Foster) Green

Will Westly echoes Posey’s point by emphasizing how everyone did their part. “I look at it like this, like a bicycle tire, a rim. You know the little spokes on there? If one of them is loose, the ride is not going to be smooth. So you got to do something to that spoke. Help everybody along. That was the neighborhood.”

Linda Dogan points out that part of what contributed to the love she felt in the neighborhood was the community’s response to a segregated society. When asked for the first word that comes to mind when she thinks about the Back of the College, Dogan didn’t hesitate: “Love. Love. And why? Because even though we were all different there was so much love for each other. And I think

Louvenia Barksdale escorted to Cumming Street School prom. Photo credit: Bertha Johnson

Bertha Johnson at Cumming Street School pageant, 1964. Photo credit: Bertha Johnson

it was because so much hate on the outside of the world. It was so much hate. So, there we have to love each other and come together and have to respect each other because nobody else was.”

The neighborhood reached its peak in the 1950s. Thriving churches were the cornerstone throughout the Northside. Four sat north and east of Wofford’s campus – Cummings Street Baptist, Walker Memorial Christian Methodist Episcopal, Greater Trinity AME and Mount Zion Baptist – and two more held down the North Dean Street area – Metropolitan AME Zion and, the original, Silver Hill Methodist. Every Sunday saw parishioners walking the neighborhood in their Sunday best and enjoying cookouts and gatherings after services.

Cumming Street School boomed under the leadership of Eugene Rivers and Emerson Coleman, who took over from Rivers in 1955. Both maintained high expectations for all students and faculty at the school. Despite the fact that the Brown vs. Board of Education decision signaled the eventual loss of Cumming Street School, the years between 1955 and 1964 saw some of its largest enrollments, with an average of 700 elementary and 300 junior high students. Teachers were committed to quality education for their students, even though during segregation teacher salaries at Cumming Street were significantly less than at white schools and educational resources were limited. Leotus Davis, an eighth-grade science teacher at Cumming Street, took students to Spartanburg’s airport and arranged for them to ride in a Cessna to learn first-hand what it meant to fly. “The pilot would point out where their schools were, circle their neighborhoods, stuff like that,” he recalled.

Teachers often visited students’ homes to report on their progress at school. Gwen Steen remembers, “[w]ell, the teachers stay on us to make sure that we did our homework. If we score low on the test, they wanted to know why. And they also visited our homes to make sure, you know, that the homes were okay. They talked to the parents. And that to me, that was an ideal education.” Teachers like Hattie Bell Penland, a 40-year veteran of teaching third grade at Cumming Street, instilled in their students the belief that they were of value and worth in this society, and to hold their head high no matter where they went.

Students worked hard in the classroom, but they also enjoyed a wide range of after school activities, including sports – Cumming Street regularly had competitive basketball and football teams – performing arts, musical theater, music programs, and big festivals like the annual May Day parade. Freda Byrd loved being in the band: “I was a music person. And so the band is what I was cut out for. And that's what I did, basically, from sixth seventh, eighth grade on through high school.”

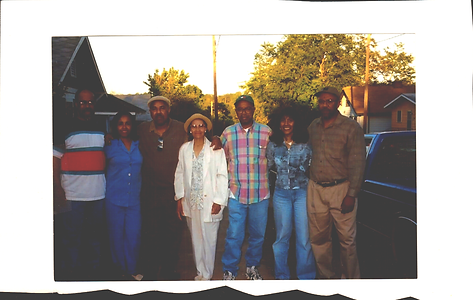

Rose Thomas, center, and family. Photo credit: Rose Thomas

The cafeteria at Cumming Street earns praise from many alumni. Leotus Davis remembered the food and atmosphere: “We all enjoyed the good meals. We all would sit around and fellowship while we had our lunch, talk to the other teachers.” And Freda Byrd loved “the big ol’ yeast rolls” served daily – as well as a bag of five Hungry Jack cookies for a penny she’d get at McBride’s store on Bell Street as she walked home after school.

Will Westly outlined several other stores in the neighborhood: “The stores we call ‘mom and pop’ stores, you know the McBride’s. And this man, I always thought he was angry. But his name was Blanco. He had a store right by Clinchfield railroad track, which was half a block from my house. There was a lady too, she probably over 100. Her store was named Julianne's. Blancos, Julianne's, McBride’s, and it was a store right by our house. And it was Keys. All of them sold like sandwiches and stuff because at that time it was no Burger Kings, no Hardees.”

Westly continued, “And I forgot about the mill store, Beaumont Mill. And it was a store call the Corner Grill. It was right next to New Method Laundry. And then it was another store they called Larry's; it was just under the underpass still on Liberty Street. And it's a man called Zack Cole and Mr. Cole had a store on Dean Street. Of course Larry's is gone, Miss Julian's gone, Blanco is gone, Keys is gone. The buildings, the structures. But still, as kids we stopped in those stores with nickels and dimes every day.”

Norma (Foster) Green, whose family had a store in the neighborhood, recalls many good cooks in the neighborhood. “I mean, it was a lot of good cooks Back of the College. I used to make my way through eating. There was one lady that used to make really good biscuits, so I dropped by her house if I thought she was cooking. There was another lady made cakes and pears and I dropped by her house

and get me something to eat. It was like always, you know, I'm dropping by people's houses, especially around during the time when I knew something was going on. We had a real close community. The bigger kids would watch out for the little ones. We used to go to T.K. Gregg with the older girls and it was just real close knit. Everybody knew everybody; everybody took care of everybody. Everybody knew who you were. If you were doing something you had no business doing, everybody got on you and told you to stop. You know, so it was a real close-knit community.”

Green continues, “We had all kinds of people. We had people from all walks of life. So we had nurses, we had teachers, we had doctors, we had people who were always doing something, we had maids. We had people who worked for the Montgomerys. Matter of fact, the Montgomery's driver used to live Back of the College and he would drive the Rolls Royce home. So it was always you know, you look down the street and there goes the Rolls Royce.

The T.K. Gregg Recreation Center was another center of the community. Doris Posey points to the basic values she learned at T.K. Gregg. “My experience at that center, I believe, taught me and people like me who went to a center like that, we learned to participate, period. We played softball; it was never an issue of who played better, who were the good players, we played softball for recreation. I believe that the children who had that experience at that center became adults who participate. I believe we join organizations, I believe we contribute, I believe we don't get overly excited when we lose. Because our experience was, you are part of a larger group, and you're not doing this to win, you're doing this to learn the sport, or whatever it is.”

Rose Thomas remembers some of T.K. Gregg’s staff. “It was a wonderful place. And Miss Eunice Thompson was the boss. She was over all of this recreation centers and kids from all around would come. It was very nice. Miss Becker and Miss Willie Hill were also there. Mr. George Lowe was there for a while. We had some good role models. We had a dress-up affair for gowns and back in the day you had to wear your long gloves and stockings, was a pantyhose stockings and your low heels. But you always wore your gloves. And it was a very nice experience.”

Just down the street from T.K. Gregg, young children of the neighborhood began their academic careers at Kiddie College, a kindergarten program run by Rev. Walter Hart and Sophia Shelton Hart. Former residents uniformly speak positively about it, like Norma (Foster) Green: “Kiddie College was interesting in that it was run by Mrs. Sophie Hart, and she had her kindergarten on Jones Street. And we actually functioned kind of like a tiny college. We had a football team. We had cheerleaders, we had a band. We had a prom. We had this yearbook, we had graduation. I had a graduation invitation. And it was, this is where I learned to read, right? We had science fairs, we had anything that a normal school would have we had, and this was two to five years old.”

Cynthia (Harris) Logan echoes Green’s memory: “Oh, Kiddie College lived up to his name. It was a kiddie college. I mean, everything we did. We had a majorette team, we had a football team. We just did everything that an actual college or high school did. We put on pageants and plays. When we graduated, we had our cap and gown!”

All these places and experiences and more show the Back of the College as the beloved community it was.

Cumming Street School choir.